How to Draw a Motte and Bailey Castle TUTORIAL

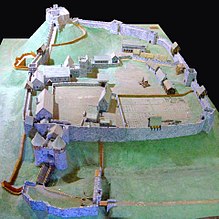

A reconstruction of the English urban center of York in the 15th century, showing the motte-and-bailey fortifications of Old Baile (left foreground) and York Castle topped by Clifford's Tower (centre right)

A motte-and-bailey castle is a European fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised area of ground called a motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or bailey, surrounded past a protective ditch and palisade. Relatively piece of cake to build with unskilled labour, merely still militarily formidable, these castles were built across northern Europe from the 10th century onwards, spreading from Normandy and Anjou in French republic, into the Holy Roman Empire in the 11th century. The Normans introduced the design into England and Wales. Motte-and-bailey castles were adopted in Scotland, Ireland, the Low Countries and Denmark in the 12th and 13th centuries. Windsor Castle, in England, is an example of a motte-and-bailey castle. By the stop of the 13th century, the pattern was largely superseded past alternative forms of fortification, but the earthworks remain a prominent feature in many countries.

Architecture [edit]

Structures [edit]

A motte-and-bailey castle was fabricated upwards of two structures: a motte (a type of mound – ofttimes artificial – topped with a wooden or stone structure known as a keep); and at least i bailey (a fortified enclosure congenital next to the motte). The term motte-and-bailey is a relatively modern one, and is not medieval in origin.[2] The word motte is the French version of the Latin mota, and in France the word motte, generally used for a clump of turf, came to refer to a turf banking concern, and by the 12th century was used to refer to the castle design itself.[3] The word "bailey" comes from the Norman-French baille, or basse-cour, referring to a low yard.[4] In medieval sources, the Latin term castellum was used to describe the bailey complex within these castles.[5]

One contemporary account of these structures comes from Jean de Colmieu around 1130, describing the Calais region in northern France. De Colmieu described how the nobles would build "a mound of world equally high every bit they tin and dig a ditch almost information technology as broad and deep every bit possible. The space on pinnacle of the mound is enclosed past a palisade of very strong hewn logs, strengthened at intervals by as many towers every bit their means tin provide. Inside the enclosure is a citadel, or keep, which commands the whole circuit of the defences. The entrance to the fortress is by means of a span, which, ascension from the outer side of the moat and supported on posts as it ascends, reaches to the elevation of the mound".[6] At Durham Castle, contemporaries described how the motte-and-bailey superstructure arose from the "tumulus of rise earth" with a keep rising "into thin air, strong within and without" with a "stalwart house...glittering with beauty in every office".[7]

Motte [edit]

Mottes were made out of earth and flattened on tiptop, and information technology tin can be very difficult to determine whether a mound is artificial or natural without excavation.[8] Some were also built over older artificial structures, such as Bronze Age barrows.[9] The size of mottes varied considerably, with these mounds beingness 3 metres to 30 metres in acme (10 feet to 100 feet), and from 30 to 90 metres (100 to 300 ft) in diameter.[ten] This minimum height of 3 metres (10 anxiety) for mottes is usually intended to exclude smaller mounds which often had not-military purposes.[11] In England and Wales, only vii% of mottes were taller than 10 metres (33 anxiety) high; 24% were between 10 and v metres (33 and 16 ft), and 69% were less than 5 metres (16 feet) tall.[12] A motte was protected past a ditch around information technology, which would typically have besides been a source of the earth and soil for constructing the mound itself.[13]

A go along and a protective wall would normally be built on top of the motte. Some walls would exist large enough to have a wall-walk around them, and the outer walls of the motte and the wall-walk could be strengthened past filling in the gap betwixt the wooden walls with earth and stones, allowing it to acquit more weight; this was chosen a garillum.[xiv] Smaller mottes could only support unproblematic towers with room for a few soldiers, whilst larger mottes could be equipped with a much grander edifice.[15] Many wooden keeps were designed with bretèches, or brattices, small balconies that projected from the upper floors of the building, allowing defenders to encompass the base of the fortification wall.[16] The early on twelfth-century chronicler Lambert of Ardres described the wooden keep on meridian of the motte at the castle of Ardres, where the "outset storey was on the surface of the ground, where were cellars and granaries, and great boxes, tuns, casks, and other domestic utensils. In the storey above were the dwelling and common living-rooms of the residents in which were the larders, the rooms of the bakers and butlers, and the great sleeping accommodation in which the lord and his wife slept...In the upper storey of the firm were garret rooms...In this storey besides the watchmen and the servants appointed to continue the business firm took their slumber".[17] Wooden structures on mottes could be protected past skins and hides to prevent them being hands set up alight during a siege.[fifteen]

Bailey [edit]

The bailey was an enclosed courtyard overlooked by the motte and surrounded by a wooden fence called a palisade and some other ditch.[18] The bailey was often kidney-shaped to fit confronting a circular motte, but could exist made in other shapes according to the terrain.[18] The bailey would contain a broad number of buildings, including a hall, kitchens, a chapel, barracks, stores, stables, forges or workshops, and was the centre of the castle's economic action.[19] The bailey was connected to the motte by a bridge, or, as often seen in England, by steps cut into the motte.[xx] Typically the ditch of the motte and the bailey joined, forming a effigy of 8 around the castle.[21] Wherever possible, nearby streams and rivers would exist dammed or diverted, creating water-filled moats, artificial lakes and other forms of water defences.[22]

In practice, in that location was a wide number of variations to this common blueprint.[23] A castle could accept more than than one bailey: at Warkworth Castle an inner and an outer bailey was constructed, or alternatively, several baileys could flank the motte, every bit at Windsor Castle.[24] Some baileys had two mottes, such as those at Lincoln.[24] Some mottes could exist square instead of round, such as at Conduce Tump (Herefordshire).[24] [25] Instead of single ditches, occasionally double-ditch defences were built, as seen at Berkhamsted.[24] Local geography and the intent of the builder produced many unique designs.[26]

Construction and maintenance [edit]

Various methods were used to build mottes. Where a natural hill could be used, scarping could produce a motte without the demand to create an artificial mound, but more commonly much of the motte would take to be constructed by paw.[20] Four methods existed for building a mound and a tower: the mound could either be built showtime, and a belfry placed on top of it; the tower could alternatively be built on the original basis surface and so cached within the mound; the tower could potentially exist congenital on the original ground surface then partially buried within the mound, the buried part forming a cellar below; or the tower could be built starting time, and the mound added subsequently.[27]

Regardless of the sequencing, bogus mottes had to exist built by piling up globe; this piece of work was undertaken by paw, using wooden shovels and manus-barrows, possibly with picks as well in the after periods.[28] Larger mottes took unduly more try to build than their smaller equivalents, because of the volumes of earth involved.[28] The largest mottes in England, such every bit Thetford, are estimated to take required upwardly to 24,000 human-days of work; smaller ones required maybe as piddling as 1,000.[29] Contemporary accounts talk of some mottes being built in a thing of days, although these low figures have led to suggestions by historians that either these figures were an underestimate, or that they refer to the construction of a smaller blueprint than that later seen on the sites concerned.[30] Taking into business relationship estimates of the likely available manpower during the period, historians estimate that the larger mottes might take taken betwixt four and ix months to build.[31] This contrasted favourably with stone keeps of the period, which typically took up to ten years to build.[32] Very little skilled labour was required to build motte and bailey castles, which fabricated them very attractive propositions if forced peasant labour was available, every bit was the case after the Norman invasion of England.[20] Where the local workforce had to be paid – such as at Clones in Ireland, built in 1211 using imported labourers – the costs would rise quickly, in this case reaching £20.[33]

A cantankerous-section showing the layers within the motte at Clifford's Tower in York: "A" marks the 20th-century physical underpinnings of the motte; the low walls enclosing the base of operations of the motte are a 19th-century addition.

The blazon of soil would make a difference to the pattern of the motte, as clay soils could support a steeper motte, whilst sandier soils meant that a motte would need a more gentle incline.[15] Where available, layers of different sorts of earth, such equally clay, gravel and chalk, would exist used alternatively to build in strength to the design.[34] Layers of turf could also be added to stabilise the motte as it was congenital up, or a core of stones placed as the heart of the structure to provide strength.[35] Similar bug practical to the defensive ditches, where designers found that the wider the ditch was dug, the deeper and steeper the sides of the scarp could be, making information technology more defensive.[15] Although militarily a motte was, as Norman Pounds describes it, "nearly indestructible", they required frequent maintenance.[36] Soil wash was a problem, peculiarly with steeper mounds, and mottes could be clad with forest or stone slabs to protect them.[20] Over time, some mottes suffered from subsidence or damage from flooding, requiring repairs and stabilisation piece of work.[37]

Although motte-and-bailey castles are the all-time-known castle design, they were non e'er the most numerous in any given surface area.[38] A popular alternative was the ringwork castle, involving a palisade being built on top of a raised earth rampart, protected past a ditch. The selection of motte and bailey or ringwork was partially driven by terrain, as mottes were typically built on low ground, and on deeper clay and alluvial soils.[39] Another factor may have been speed, as ringworks were faster to build than mottes.[twoscore] Some ringwork castles were later converted into motte-and-bailey designs, by filling in the centre of the ringwork to produce a flat-topped motte.[41] The reasons for why this decision was taken are unclear; motte-and-bailey castles may have been felt to be more than prestigious, or easier to defend; some other theory is that like the terpen in kingdom of the netherlands, or Vorburg and Hauptburg in Lower Rhineland, raising the height of the castle was done to create a drier site.[41]

History [edit]

Emergence of the blueprint [edit]

The motte-and-bailey castle is a peculiarly northern European phenomenon, most numerous in Normandy and United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, only besides seen in Denmark, Germany, Southern Italy and occasionally beyond.[42] European castles starting time emerged in the ninth and 10th centuries, after the fall of the Carolingian Empire resulted in its territory being divided among private lords and princes and local territories became threatened by the Magyars and the Norse.[43] Against this background, various explanations accept been put forward to explicate the origins and spread of the motte-and-bailey blueprint across northern Europe; in that location is often a tension amid the academic customs between explanations that stress war machine and social reasons for the rise of this blueprint.[44] One proffer is that these castles were built particularly in order to protect against external assail – the Angevins, it is argued, began to build them to protect against the Viking raids, and the pattern spread to deal with the attacks along the Slav and Hungarian frontiers.[45] Some other statement is that, given the links between this style of castle and the Normans, who were of Viking descent, it was in fact originally a Viking blueprint, transported to Normandy and Anjou.[46] The motte-and-bailey castle was certainly effective against assault, although as historian André Debord suggests, the historical and archaeological record of the military operation of motte-and-bailey castles remains relatively limited.[47]

An alternative approach focuses on the links between this course of castle and what can be termed a feudal way of society. The spread of motte-and-bailey castles was usually closely tied to the creation of local fiefdoms and feudal landowners, and areas without this method of governance rarely built these castles.[48] Even so another theory suggests that the design emerged as a event of the pressures of space on ringworks and that the earliest motte-and-baileys were converted ringworks.[49] [nb 1] Finally, at that place may be a link between the local geography and the building of motte-and-bailey castles, which are usually built on low-lying areas, in many cases bailiwick to regular flooding.[50] Regardless of the reasons behind the initial popularity of the motte-and-bailey pattern, however, there is widespread understanding that the castles were first widely adopted in Normandy and Angevin territory in the tenth and 11th centuries.[51]

Initial development, 10th and 11th centuries [edit]

The earliest purely documentary evidence for motte-and-bailey castles in Normandy and Angers comes from between 1020 and 1040, merely a combination of documentary and archaeological evidence pushes the date for the first motte and bailey castle, at Vincy, back to 979.[3] The castles were congenital by the more powerful lords of Anjou in the late 10th and 11th centuries, in detail Fulk 3 and his son, Geoffrey II, who built a not bad number of them between 987 and 1060.[52] Many of these earliest castles would have appeared quite crude and rustic by later standards, belying the power and prestige of their builders.[53] William the Conquistador, every bit the Knuckles of Normandy, is believed to have adopted the motte-and-bailey pattern from neighbouring Anjou.[54] Duke William went on to prohibit the building of castles without his consent through the Consuetudines et Justicie, with his legal definition of castles centring on the classic motte-and-bailey features of ditching, banking and palisading.[55]

By the 11th century, castles were built throughout the Holy Roman Empire, which then spanned central Europe. They at present typically took the form of an enclosure on a hilltop, or, on lower ground, a tall, free-standing tower (German Bergfried).[56] The largest castles had well-defined inner and outer courts, but no mottes.[57] The motte-and-bailey design began to spread into Alsace and the northern Alps from France during the first one-half of the 11th century, spreading further into Bohemia and Austria in the subsequent years.[58] This form of castle was closely associated with the colonisation of newly cultivated areas inside the Empire, equally new lords were granted lands by the emperor and built castles close to the local gród, or boondocks.[59] Motte-and-bailey castle edifice substantially enhanced the prestige of local nobles, and information technology has been suggested that their early on adoption was considering they were a cheaper way of imitating the more prestigious Höhenburgen built on high basis, but this is normally regarded every bit unlikely.[lx] In many cases, bergfrieds were converted into motte and bailey designs past burial existing castle towers within the mounds.[threescore]

In England, William invaded from Normandy in 1066, resulting in three phases of castle building in England, around lxxx% of which were in the motte-and-bailey pattern.[61] The first of these was the establishment by the new king of royal castles in key strategic locations, including many towns.[62] These urban castles could make use of the existing town's walls and fortification, but typically required the demolition of local houses to make infinite for them.[63] This could cause extensive harm: records suggest that in Lincoln 166 houses were destroyed, with 113 in Norwich and 27 in Cambridge.[64] The second and third waves of castle building in the late-11th century were led by the major magnates and so the more junior knights on their new estates.[65] Some regional patterns in castle building can be seen – relatively few castles were built in East Anglia compared to the west of England or the Marches, for example; this was probably due to the relatively settled and prosperous nature of the east of England and reflected a shortage of unfree labour for constructing mottes.[66] In Wales, the outset moving ridge of the Norman castles was again predominantly fabricated of wood in a mixture of motte-and-bailey and ringwork designs.[67] The Norman invaders spread up the valleys, using this form of castle to occupy their new territories.[68] After the Norman conquest of England and Wales, the building of motte-and-bailey castles in Normandy accelerated equally well, resulting in a broad swath of these castles across the Norman territories, effectually 741 motte-and-bailey castles in England and Wales lone.[69]

Further expansion, 12th and 13th centuries [edit]

A vliedburg motte in the netherlands

Having become well established in Normandy, Deutschland and Britain, motte-and-bailey castles began to be adopted elsewhere, mainly in northern Europe, during the twelfth and 13th centuries. Conflict through the Low Countries encouraged castle edifice in a number of regions from the late 12th century to the 14th century.[lxx] In Flemish region, the first motte and bailey castles began relatively early at the finish of the 11th century.[71] The rural motte-and-bailey castles followed the traditional design, but the urban castles ofttimes lacked the traditional baileys, using parts of the town to fulfil this part instead.[72] Motte-and-bailey castles in Flanders were especially numerous in the south along the Lower Rhine, a fiercely contested border.[73] Further along the declension in Friesland, the relatively decentralised, egalitarian society initially discouraged the building of motte and bailey castles, although terpen, raised "home mounds" which lacked towers and were ordinarily lower in height than a typical motte, were created instead.[74] By the cease of the medieval period, however, the terpen gave way to hege wieren, non-residential defensive towers, ofttimes on motte-similar mounds, endemic past the increasingly powerful nobles and landowners.[74] On Zeeland the local lords had a high degree of independence during the 12th and 13th centuries, attributable to the wider conflict for ability between neighbouring Flanders and Friesland.[75] The Zeeland lords had also built terpen mounds, but these gave way to larger werven constructions–effectively mottes–which were later termed bergen.[76] Sometimes both terpen and werven are chosen vliedburg, or "refuge castles".[77] During the twelfth and 13th centuries a number of terpen mounds were turned into werven mottes, and some new werven mottes were built from scratch.[78] Around 323 known or probable motte and bailey castles of this pattern are believed to have been congenital inside the borders of the modern Netherlands.[11]

In neighbouring Denmark, motte-and-bailey castles appeared somewhat afterwards in the 12th and 13th centuries and in more limited numbers than elsewhere, due to the less feudal society.[79] Except for a handful of mote and bailey castles in Kingdom of norway, built in the first half of the 11th century and including the royal residence in Oslo, the design did not play a role further northward in Scandinavia.[80]

The Norman expansion into Wales slowed in the 12th century just remained an ongoing threat to the remaining native rulers. In response, the Welsh princes and lords began to build their own castles, frequently motte-and-bailey designs, ordinarily in wood.[81] At that place are indications that this may have begun from 1111 onwards under Prince Cadwgan ap Bleddyn, with the first documentary evidence of a native Welsh castle beingness at Cymmer in 1116.[82] These timber castles, including Tomen y Rhodywdd, Tomen y Faerdre, Gaer Penrhôs, were of equivalent quality to the equivalent Norman fortifications in the area, and information technology can evidence difficult to distinguish the builders of some sites from the archaeological evidence alone.[83]

Motte-and-bailey castles in Scotland emerged equally a consequence of the centralising of royal authority in the 12th century.[84] David I encouraged Norman and French nobles to settle in Scotland, introducing a feudal mode of landholding and the use of castles as a way of controlling the contested lowlands.[85] The quasi-independent polity of Galloway, which had resisted the rule of David and his predecessors, was a detail focus for this colonisation.[86] The size of these Scottish castles, primarily wooden motte and bailey constructions, varied considerably, from larger designs such equally the Bass of Inverurie to smaller castles like Balmaclellan.[87]

Motte-and-bailey castles were introduced to Ireland following the Norman invasion of Ireland that began between 1166 and 1171 under first Richard de Clare and then Henry II of England, with the occupation of southern and eastern Ireland by a number of Anglo-Norman barons.[88] The rapid Norman success depended on key economic and armed forces advantages; their cavalry enabled Norman successes in battles, and castles enabled them to control the newly conquered territories.[89] The new lords rapidly congenital castles to protect their possessions; nearly of these were motte-and-bailey constructions, many of them strongly defended.[xc] Unlike Wales, the indigenous Irish gaelic lords do not appear to have constructed their own castles in whatever significant number during the period.[91] [nb 2] Betwixt 350 and 450 motte-and-bailey castles are believed to remain today, although the identification of these earthwork remains tin can be contentious.[93]

A small number of motte-and-bailey castles were built exterior of northern Europe. In the late-12th century, the Normans invaded southern Italy and Sicily; although they had the technology to build more modernistic designs, in many cases wooden motte-and-bailey castles were built instead for reasons of speed.[94] The Italians came to refer to a range of different castle types every bit motta, yet, and there may not have been as many 18-carat motte-and-bailey castles in southern Italian republic as was in one case idea on the basis of the documentary show alone.[95] In addition, in that location is bear witness of the Norman crusaders edifice a motte and bailey using sand and forest in Arab republic of egypt in 1221 during the Fifth Crusade.[96]

Conversion and turn down, 13th–14th centuries [edit]

Motte-and-bailey castles became a less popular design in the mid-medieval period. In France, they were non congenital after the start of the 12th century, and mottes ceased to be built in nearly of England after effectually 1170, although they continued to be erected in Wales and along the Marches.[97] Many motte-and-bailey castles were occupied relatively briefly; in England, many had been abandoned or allowed to lapse into disrepair by the twelfth century.[98] In the Low Countries and Germany, a like transition occurred in the 13th and 14th centuries.

I factor was the introduction of rock into castle building. The earliest rock castles had emerged in the 10th century, with stone keeps beingness built on mottes along the Catalonia frontier and several, including Château de Langeais, in Angers.[99] Although wood was a more powerful defensive material than was one time thought, rock became increasingly popular for military and symbolic reasons.[100] Some existing motte-and-bailey castles were converted to stone, with the keep and the gatehouse usually the starting time parts to be upgraded.[101] Shell keeps were built on many mottes, round stone shells running effectually the top of the motte, sometimes protected by a farther chemise, or low protective wall, around the base. By the 14th century, a number of motte and bailey castles had been converted into powerful stone fortresses.[102]

A reconstruction of England'south Carisbrooke Castle on the Island of Wight every bit it was in the 14th century, showing the keep built atop the motte (pinnacle left), and the walled-in bailey beneath

Newer castle designs placed less emphasis on mottes. Square Norman keeps built in rock became pop post-obit the first such construction in Langeais in 994. Several were built in England and Wales after the conquest; past 1216 there were effectually 100 in the country.[103] These massive keeps could be either erected on superlative of settled, well-established mottes or could take mottes built around them – and so-called "buried" keeps.[104] The ability of mottes, particularly newly built mottes, to support the heavier stone structures, was limited, and many needed to be built on fresh ground.[105] Concentric castles, relying on several lines of baileys and defensive walls, made increasingly picayune use of keeps or mottes at all.[106]

Across Europe, motte-and-bailey construction came to an terminate. At the end of the 12th century the Welsh rulers began to build castles in stone, primarily in the principality of North Wales and unremarkably forth the college peaks where mottes were unnecessary.[82] In Flanders, reject came in the 13th century as feudal social club changed.[71] In the netherlands, cheap brick started to exist used in castles from the 13th century onwards in place of excavation, and many mottes were levelled, to help develop the surrounding, low-lying fields; these "levelled mottes" are a especially Dutch phenomenon.[107] In Denmark, motte and baileys gave way in the 14th century to a castrum-curia model, where the castle was built with a fortified bailey and a fortified mound, somewhat smaller than the typical motte.[108] By the 12th century, the castles in Western Germany began to sparse in number, due to changes in land ownership, and various mottes were abased.[109] In Frg and Kingdom of denmark, motte-and-bailey castles also provided the model for the after wasserburg, or "water castle", a stronghold and bailey construction surrounded by water, and widely built in the late medieval period.[110]

Today [edit]

In England, motte-and-bailey earthworks were put to various uses over later on years; in some cases, mottes were turned into garden features in the 18th century, or reused as military defences during the Second World War.[111] Today, nigh no mottes of motte-and-bailey castles remain in regular utilise in Europe, with one of the few exceptions being that at Windsor Castle, converted for the storage of royal documents.[112] Some other example is Durham Castle in northern England, where the round tower is used for student accommodation. The landscape of northern Europe remains scattered with their excavation, and many form popular tourist attractions.

Encounter likewise [edit]

- Castles in Slap-up Britain and Ireland

- List of castles and palaces in Kingdom of denmark

- List of castles in Belgium

- List of castles in France

- Listing of castles in Frg

- Listing of castles in the Netherlands

- List of motte-and-bailey castles

- Motte-and-bailey fallacy

- Mueang for similar fortifications of the same era in Southeast Asia

Notes [edit]

- ^ Ringworks crave an inner scarp, or sloping confront; this means that the interior space is always less than a apartment-topped motte of equivalent height and width. In-filling ringworks certainly occurred later, and may have been the initial step likewise.[49]

- ^ There has been some contend over the absence of indigenous Irish castle building. Irish castle specialist Tom McNeill has noted that information technology would appear very strange if the indigenous Irish lords had not adopted castle engineering science during their long struggle with the Anglo-Norman nobility, merely there is no meaning archaeological or historical evidence to testify such construction.[92]

References [edit]

- ^ Historic England. "Castle Pulverbatch motte and bailey castle with outer bailey, 100m NNW of Brook Cottage (1012860)". National Heritage List for England . Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ Besteman, p.212.

- ^ a b King (1991), p.38.

- ^ Lepage, p.34.

- ^ Pounds, p.22.

- ^ Toy, p.53.

- ^ Kenyon, p.13 citing Armitage 1912: pp.147-8.

- ^ Toy, p.52; Chocolate-brown (1962), p.24.

- ^ Kenyon, pp.9-10.

- ^ Toy, p.52.

- ^ a b Besteman, p.213.

- ^ Kenyon, p.4, citing King (1972), pp.101-2.

- ^ Dark-brown (1962), p.29.

- ^ King (1991), p.55.

- ^ a b c d DeVries, p.209.

- ^ Rex (1991), pp.53-iv.

- ^ Chocolate-brown (1962), p.30.

- ^ a b DeVries, p.211.

- ^ Meulemeester, p.105; Cooper, p.18; Butler, p.xiii.

- ^ a b c d Pounds, p.17.

- ^ Brown (1962), p.24.

- ^ Brown (1989), p.23.

- ^ Brown (1962), p.26.

- ^ a b c d DeVries, p.212.

- ^ Male monarch (1972), p.106.

- ^ Liddiard (2005), p.42.

- ^ King (1991), pp. fifty–51.

- ^ a b Pounds, p. 18.

- ^ Pounds, p. nineteen.

- ^ Brown (2004), p. 110; Cooper, p. 15.

- ^ Kenyon, p. 7.

- ^ Pounds, p. 20.

- ^ McNeill, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Kenyon, p. 11.

- ^ Kenyon, p. 10.

- ^ Pounds, p. 21.

- ^ Cooper, p. 76; Butler, p. 17.

- ^ Van Houts, p. 61.

- ^ Pounds, p. 17; Creighton, p. 47.

- ^ Creighton, p. 47.

- ^ a b Pounds, p. 14.

- ^ Pringle, p.187; Toy, p.52.

- ^ King (1991), p.34.

- ^ Debord, pp.93-four.

- ^ Nicolle, p.33; Kaufmann and Kaufmann, p.109.

- ^ Nicholson, p.77; Kaufmann and Kaufmann, p.109.

- ^ Brown (1962), pp.28-9; Debord, p.95.

- ^ Lepage, p.35; Collardelle and Mazard, pp.72-3.

- ^ a b King (1991), p.37.

- ^ DeVries, p.202.

- ^ Kaufmann and Kaufmann, p.109; Nicolle, p.33.

- ^ DeVries, pp.203-4.

- ^ Héricher, p.97.

- ^ DeVries, p.204.

- ^ King (1991), p.35.

- ^ Kaufmann and Kaufmann, p.109.

- ^ Purton, p.195.

- ^ Purton, pp.195-6; Collardelle and Mazard, pp.71, 78; Jansen, p.195; Kaufmann and Kaufmann, p.110.

- ^ Collardelle and Mazard, pp.71, 78; Jansen, p.195; Kaufmann and Kaufmann, p.110..

- ^ a b Purton, p.196.

- ^ Liddiard (2005), p.17; Creighton (2005), p.48.

- ^ Liddiard (2005), p.eighteen; Brown (1962), p.22.

- ^ Liddiard (2005), p.19; Brown (1962), p.22.

- ^ Brownish (1962), p.22; Pounds (1994), p.208.

- ^ Liddiard (2005), pp.18, 23.

- ^ Liddiard (2005), p.25.

- ^ Pettifer, p.13.

- ^ King (1991), pp.139-141.

- ^ Liddiard (2005), p.23; King (1991), p.47.

- ^ Besteman, p.217; Kenyon, p.eight.

- ^ a b Meulemeester, p.103.

- ^ Meulemeester, p.102.

- ^ Besteman, p.219.

- ^ a b Besteman, p.215.

- ^ Besteman, p.217.

- ^ King (1991), p.39; Besteman, p.216.

- ^ Nicholson, p.77.

- ^ Besteman, p.216.

- ^ Stiesdal, pp.210, 213; Kenyon, p.eight.

- ^ Ekroll, p.66.

- ^ Pettifer, p. 14.

- ^ a b Rex (1991), p.130.

- ^ Pettifer, p.14.

- ^ Simpson and Webster, p.225.

- ^ Simpson and Webster, p.225; Tabraham, p.11.

- ^ Simpson and Webster, p.231.

- ^ Tabraham, p.sixteen.

- ^ McNeill, p.17.

- ^ Carpenter, pp.220-1.

- ^ Carpenter, p.221; O'Conor, pp.173, 179.

- ^ McNeill, pp.74, 84.

- ^ McNeill, p.84.

- ^ O'Conor, p.173.

- ^ Purton, 180.

- ^ Pringle, p.187.

- ^ Pringle, p.190.

- ^ Pounds, p.21; Châtelain, p.231.

- ^ Pounds, pp.twenty-1; Kenyon, p.17; Meulemeester, p.104.

- ^ Nicholson, p.78; Kaufmann and Kaufmann, p.109.

- ^ Liddiard (2005), p.53; King (1991), p.62.

- ^ Brown (1962), p.38.

- ^ King (1991), pp.62-65

- ^ Hulme, p.213; King (1991), p.36.

- ^ Bradbury, p.121.

- ^ Kaufmann and Kaufmann, p.111.

- ^ King (1991), p.94.

- ^ Besteman, p.214; Kenyon, p.viii.

- ^ Stiesdal, p.214.

- ^ Collardelle and Mazard, p.79.

- ^ Jansen, p.197.

- ^ Creighton, pp.85-6; Lowry, p.23; Creighton and Higham, p.62.

- ^ Robinson, p.142.

Bibliography [edit]

- Armitage, Ella S. (1912) The Early Norman Castles of the British isles. London: J. Murray. OCLC 458514584.

- Besteman, Jan. C. (1984) "Mottes in the Netherland," in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. XII. pp. 211–224.

- Bradbury, Jim. (2009) Stephen and Matilda: the Ceremonious War of 1139-53. Stroud, UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-3793-one.

- Dark-brown, R. Allen. (1962) English Castles. London: Batsford. OCLC 1392314.

- Brown, R. Allen. (1989) Castles From the Air. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-32932-three.

- Brown, R. Allen. (2004) Allen Dark-brown'south English Castles. Woodbridge, United kingdom: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-069-half dozen.

- Butler, Lawrence. (1997) Clifford'south Tower and the Castles of York. London: English Heritage. ISBN 1-85074-673-seven.

- Carpenter, David. (2004) Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of U.k. 1066–1284. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-014824-four.

- Châtelain, André. (1983) Châteaux Forts et Féodalité en Ile de France, du XIème au XIIIème siècle. Nonette: Créer. ISBN 978-2-902894-16-i. (in French)

- Colardelle, Michel and Chantal Mazard. (1982) "Les mottes castrales et fifty'évolution des pouvoirs dans le Alpes du Nord. Aux origines de la seigneurie," in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. XI, pp69–89. (in French)

- Cooper, Thomas Parsons. (1911) The History of the Castle of York, from its Foundation to the Current Solar day with an Account of the Building of Clifford's Tower. London: Elliot Stock. OCLC 4246355.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton. (2005) Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London: Equinox. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton and Robert Higham. (2003) Medieval Castles. Princes Risborough, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0-7478-0546-5.

- Debord, André. (1982) "A propos de l'utilisation des mottes castrales," in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. 11, pp91–99. (in French)

- DeVries, Kelly. (2003) Medieval Military machine Technology. Toronto, Canada: Academy of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-921149-74-3.

- Ekroll, Oystein. (1996) "Norwegian medieval castles: building on the edge of Europe," in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. Xviii, pp65–73.

- Héricher, Anne-Marie Flambard. (2002) "Fortifications de terre et résidences en Normandie," in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. 20 pp87–100. (in French)

- Hulme, Richard (2008), "12th Century Great Towers - The Case for the Defence" (PDF), The Castle Studies Group Periodical, 21: 209–229

- Jansen, Walter. (1981) "The international background of castle building in Key Europe," in Skyum-Nielsen and Lund (eds) (1981).

- Kaufmann, J. E. and H. W. Kaufmann. (2004) The Medieval Fortress: castles, forts and walled cities of the Centre Ages. Cambridge, US: Da Capo. ISBN 978-0-306-81358-0.

- Kenyon, John R. (2005) Medieval Fortifications. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-7886-3.

- Male monarch, D. J. Cathcart. (1972) "The field archaeology of mottes in England and Wales: eine kurze übersichte," in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. V, pp. 107–111

- King, D. J. Cathcart. (1991) The Castle in England and Wales: An Interpretative History. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00350-four.

- Lepage, Jean-Denis. (2002) Castles and Fortified Cities of Medieval Europe: an illustrated history. Jefferson, Usa: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1092-7.

- Liddiard, Robert. (ed) (2003a) Anglo-Norman Castles. Woodbridge, Great britain: Boydell Printing. ISBN 978-0-85115-904-one.

- Liddiard, Robert. (2005) Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Mural, 1066 to 1500. Macclesfield, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Windgather Press. ISBN 0-9545575-two-ii.

- Lowry, Bernard. Discovering Fortifications: From the Tudors to the Cold War. Risborough, UK: Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0-7478-0651-half dozen.

- McNeill, Tom. (2000) Castles in Ireland: Feudal Power in a Gaelic World. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22853-4.

- De Meulemeester, Johnny. (1982) "Mottes Castrales du Comté de Flandres: État de la question d'april les fouilles récent," Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. XI, pp101–115. (in French)

- Nicolle, David. (1984) The Historic period of Charlemagne. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-0-85045-042-2.

- Nicholson, Helen J. (2004) Medieval Warfare: theory and practice of war in Europe, 300-1500. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-76330-8.

- O'Conor, Kieran. (2002) "Motte Castles in Ireland, Permanent fortresses, Residences and Manorial Centres," in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. XX, pp173–182. (in French)

- Pettifer, Adrian. (2000) Welsh Castles: a Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Printing. ISBN 978-0-85115-778-8.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1994) The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a social and political history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- Pringle, Denys. "A castle in the sand: mottes in the Crusader east," in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. Eighteen, pp187–190.

- Purton, Peter. (2009) A History of the Early Medieval Siege, c.450-1200. Woodbridge, Uk: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-ane-84383-448-9.

- Robinson, John Martin. (2010) Windsor Castle: the Official Illustrated History. London: Royal Collection Publications. ISBN 978-1-902163-21-five.

- Skyum-Nielsen, Niels and Niels Lund (eds) (1981) Danish Medieval History: New Currents. Københavns, Kingdom of denmark: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-88073-30-0.

- Simpson, Grant G. and Bruce Webster. (2003) "Charter Prove and the Distribution of Mottes in Scotland," in Liddiard (ed) (2003a).

- Stiesdal, Hans. (1981) "Types of public and individual fortifications in Kingdom of denmark," in Skyum-Nielsen and Lund (eds) (1981).

- Tabraham, Chris J. (2005) Scotland's Castles. London: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-8943-nine.

- Toy, Sidney. (1985) Castles: Their Construction and History. ISBN 978-0-486-24898-ane.

- Van Houts, Elisabeth Thousand. C. (2000) The Normans in Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4751-0.

External links [edit]

- Mottes: a type of castle or simply an element of some castles? A century of motte studies (2021) talk by Dr. Tom McNeill for the Castle Studies Group

DOWNLOAD HERE

How to Draw a Motte and Bailey Castle TUTORIAL

Posted by: aaronhoseverve1996.blogspot.com

Comments

Post a Comment